Lorenzo De Sio and Davide Angelucci have recently published a research paper titled “The Cultural (Even More Than Political) Legacy of Entertainment TV,” in which they investigate the long-term effects of early exposure to entertainment television (particularly Mediaset) on citizens’ values. This topic is especially relevant for POSTGEN, as it suggests the importance of non-political content for shaping values of citizens, with an indirect but relevant effect also on political attitudes.

Below the translation of a short interview by Matteo Boldrini to the two authors, published on the CISE website.

The effects of television on opinions, particularly political opinions, and hence on voting, was a much-discussed topic in the 1990s, following Berlusconi’s entry into politics. However, today we can say that it doesn’t seem to be a very current topic. Where did the idea for the article come from?

Lorenzo De Sio: Well, actually, that’s true… the idea came to us a few years ago after reading a study on the subject by some researchers from Bocconi University [Durante, Pinotti, and Tesei, ed.]. They had collected very interesting data on the strength of Mediaset (formerly Fininvest) antennas in the early 1980s and combined them with data on mountain reliefs throughout Italy. Thus, they reconstructed which Italian municipalities could already receive Berlusconi’s networks (initially only Canale 5) starting from 1979 and which ones received them only years later. By linking these data with survey data collected several years later, they tested whether there were differences in people’s opinions in cities that had received Mediaset for more years compared to others. They discovered that indeed there was a slight but noticeable tendency to have more “populist” opinions, to vote for Forza Italia, or even to vote for the Five Star Movement in 2013, thirty years later….

I remember this study from years ago. It was quite controversial and sparked a debate in which even journalist Enrico Mentana [currently anchor of an important evening news programme, and a former Mediaset anchor] took a critical stance…

Indeed. The data was actually solid (although with not very strong effects), but the controversy arose because the authors argued that one of the effects of Mediaset was the lowering of cognitive levels due to low-quality programming, which would predispose people toward populist attitudes. This sparked a heated debate. We started from this point because the data was interesting and the results were solid, but there was something that didn’t convince us about the explanatory mechanism.

What exactly did you disagree with regarding the explanation offered by the Bocconi researchers?

Davide Angelucci: In our opinion, the real cause was not the lowering of cognitive levels. From many electoral studies, we know clearly that Forza Italia, over the decades, was able to mobilize voters around specific issues, such as specific economic preferences (e.g., protecting self-employed workers and businesses), even across different social classes and not only among the less educated or politically disengaged individuals. So, in our view, the mechanism behind the media exposure effect of Mediaset had to be somewhat different. Also: in that period, the early 1980s, Mediaset, among other things, presented exclusively entertainment content. The point, is that these programs promoted specific lifestyles and values that were very different from those promoted by the Rai public television, which even in entertainment had a quite pedagogical approach linked to traditional and solidaristic values.

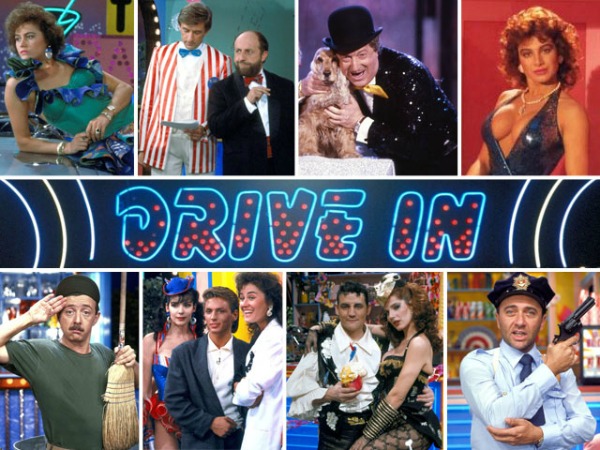

LDS (interrupting): … I was a kid in those years, and I remember them well: series like Dallas [which initially started with a few episodes on Rai but was quickly canceled and moved to Mediaset, where it was successfully broadcasted for many years, ed.] and Dynasty, with individualistic, luxurious, and morally uninhibited lifestyles… programs like OK il prezzo è giusto (adapted from the American The Price Is Right), which celebrated consumerism; comedy shows with prosperous pin-up girls, like Drive In… all things that one would never see on Rai, to the extent that one of the most famous programs on Mediaset (although a few years later) would be called Non è la Rai [“This is not Rai”]…

DA: Here’s the idea: entertainment programs also convey lifestyles and, therefore, values. Thus, exposure to these programs can have an impact on citizens and their values. From this perspective, we have built our argument based on a solid scientific literature showing how individuals differ in a variety of values that also influence politics and voting choices. In this sense, our idea revolves around the fact that the impact of increased exposure to Mediaset is not linked to a decline in citizens’ cognitive abilities but rather to its ability to influence the reference values of many of these citizens.

Right, but… how can you measure the different values that people believe in?

LDS: The real challenge lies in this aspect. However, there has been extensive research, especially in psychology, on this matter. Research on people’s values has developed measurement scales that are administered in numerous surveys. A particularly fascinating contribution comes from Israeli psychologist Shalom Schwartz, who in the 1990s proposed a series of questions to assess individuals’ orientations towards ten different core values. For example, these values include the importance of hedonism, power achievement, success, conformity, benevolence towards others, and so on. We specifically recalled that these questions were included in a survey conducted by the ITANES research group [which also involved CISE scholars] on a sample of Italians in 2006. At that point, we linked the ITANES data on citizens’ values with the data on Mediaset accessibility (by municipality) in the early 1980s, collected by researchers from Bocconi University. We then identified which respondents lived in cities and towns that had received Mediaset broadcasts for five or six more years in the early 1980s, to find out if, twenty years later, their opinions were actually somewhat different from those of others. Essentially, we replicated the analysis conducted by our colleagues, but specifically examining the impact on values. With the underlying idea that even if those respondents themselves may not have personally watched Mediaset networks (perhaps because they were too young), their families, neighbors, schoolmates, or coworkers did, thus effectively influencing the value orientations of entire communities.

And so, what were the results?

DA: The results are extremely interesting. We found that exposure to Mediaset, particularly long-term exposure, had a significantly broader and statistically stronger impact on respondents’ values compared to what our colleagues found regarding populism. Respondents living in cities with more long-term Mediaset accessibility show more individualistic and conservative tendencies than others. This seems to support our thesis that the cultural legacy of entertainment television appears to be stronger than its political implications and likely predates them. This doesn’t mean that this phenomenon lacks political implications, but it also has broader implications for cultural transformations and values. It’s worth noting that during the crucial period for our analysis, when Mediaset was only available in certain cities (the early 1980s), it focused exclusively on entertainment programming without any political or news content. This leads us to reflect on the importance, in a democratic system, of ensuring a plurality of worldviews, even in non-directly political content.

But today people (especially the younger), don’t use TV as much. Does your research still have relevant implications?

LDS: This is an important point. In fact, we know: 1) that TV remains highly relevant for various segments of the population, but more importantly, 2) that TV content is now distributed in many different ways, such as through streaming, including on mobile devices, and that’s why they continue to be very popular and significant. For example, a highly popular series among young people in Italy, named “Mare Fuori,” paradoxically achieved more success through streaming than on terrestrial TV. Additionally, a lot of TV content circulates widely through social media, highlighting the continued importance of TV. But above all, the significance of non-political programs in influencing values must be emphasized. Since we found significant effects even after a twenty-year span, the question is: what values are being conveyed by all the media content we are immersed in? And what impact do they have on our values? Even for comedy shows like “LOL” and for series available on Netflix: what impact do they have on our values?

Furthermore, this is of even broader relevance. Within the POSTGEN project we are starting to study the potential impact of influencers on social media on politics (including non-political influencers such as Chiara Ferragni). More broadly, this should make us reflect on the issue of pluralism, which involves the representation of different values, even in entertainment programs and on social media. Therefore, a research agenda for the future is to examine the types of values associated with the most widespread content, to understand if we are being strongly influenced in a certain direction, of which we may not yet be aware.